Whitney embedding theorem

In mathematics, particularly in differential topology, there are two Whitney embedding theorems:

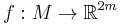

- The strong Whitney embedding theorem states that any smooth m-dimensional manifold (required also to be Hausdorff and second-countable) can be smoothly embedded in Euclidean

-space, if m>0. This is the best linear bound on the smallest-dimensional Euclidean space that all m-dimensional manifolds embed in, as the real projective spaces of dimension

-space, if m>0. This is the best linear bound on the smallest-dimensional Euclidean space that all m-dimensional manifolds embed in, as the real projective spaces of dimension  cannot be embedded into Euclidean (

cannot be embedded into Euclidean ( )-space if m is a power of two (as can be seen from a characteristic class argument, also due to Whitney).

)-space if m is a power of two (as can be seen from a characteristic class argument, also due to Whitney).

- The weak Whitney embedding theorem states that any continuous function from an n-dimensional manifold to an m-dimensional manifold may be approximated by a smooth embedding provided m>2n. Whitney similarly proved that such a map could be approximated by an immersion provided m>2n-1. This last result is sometimes called the weak Whitney immersion theorem.

Contents |

A little about the proof

The general outline of the proof is to start with an immersion  with transverse self-intersections. These are known to exist from Whitney's earlier work on the weak immersion theorem. Transversality of the double points follows from a general-position argument. The idea is to then somehow remove all the self-intersections. If

with transverse self-intersections. These are known to exist from Whitney's earlier work on the weak immersion theorem. Transversality of the double points follows from a general-position argument. The idea is to then somehow remove all the self-intersections. If  has boundary, one can remove the self-intersections simply by isotoping

has boundary, one can remove the self-intersections simply by isotoping  into itself (the isotopy being in the domain of

into itself (the isotopy being in the domain of  ), to a submanifold of

), to a submanifold of  that does not contain the double-points. Thus, we are quickly led to the case where

that does not contain the double-points. Thus, we are quickly led to the case where  has no boundary. Sometimes it is impossible to remove the double-points via an isotopy—consider for example the figure-8 immersion of the circle in the plane. In this case, one needs to introduce a local double point. Once one has two opposite double points, one constructs a closed loop connecting the two, giving a closed path in

has no boundary. Sometimes it is impossible to remove the double-points via an isotopy—consider for example the figure-8 immersion of the circle in the plane. In this case, one needs to introduce a local double point. Once one has two opposite double points, one constructs a closed loop connecting the two, giving a closed path in  . Since

. Since  is simply-connected, one can assume this path bounds a disc, and provided

is simply-connected, one can assume this path bounds a disc, and provided  one can further assume (by the weak Whitney embedding theorem) that the disc is embedded in

one can further assume (by the weak Whitney embedding theorem) that the disc is embedded in  such that it intersects the image of

such that it intersects the image of  only in its boundary. Whitney then uses the disc to create a 1-parameter family of immersions, in effect pushing

only in its boundary. Whitney then uses the disc to create a 1-parameter family of immersions, in effect pushing  across the disc, removing the two double points in the process. In the case of the figure-8 immersion with its introduced double-point, the push across move is quite simple (pictured). This process of eliminating opposite sign double-points by pushing the manifold along a disc is called the Whitney Trick.

across the disc, removing the two double points in the process. In the case of the figure-8 immersion with its introduced double-point, the push across move is quite simple (pictured). This process of eliminating opposite sign double-points by pushing the manifold along a disc is called the Whitney Trick.

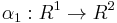

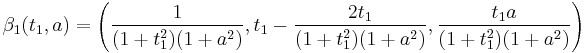

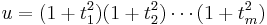

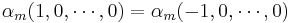

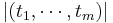

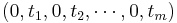

To introduce a local double point, Whitney created a family of immersions  of

of  into

into  which are approximately linear outside of the unit ball, but containing a single double point. For

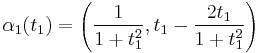

which are approximately linear outside of the unit ball, but containing a single double point. For  such an immersion is defined as

such an immersion is defined as  with

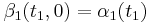

with  . Notice that if

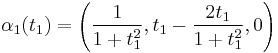

. Notice that if  is considered as a map to

is considered as a map to  i.e.:

i.e.:  then the double point can be resolved to an embedding:

then the double point can be resolved to an embedding:  . Notice

. Notice  and for

and for  then as a function of

then as a function of  ,

,  is an embedding. Define

is an embedding. Define  .

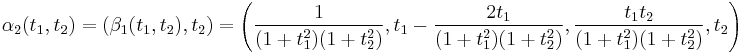

.  can similarly be resolved in

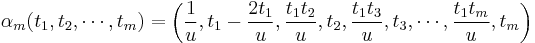

can similarly be resolved in  , this process ultimately leads one to the definition:

, this process ultimately leads one to the definition:  with

with  for all

for all  . The key properties of

. The key properties of  is that it is an embedding except for the double-point

is that it is an embedding except for the double-point  . Moreover, for

. Moreover, for  large, it is approximately the linear embedding

large, it is approximately the linear embedding  .

.

Eventual consequences of the Whitney trick

The Whitney trick was used by Steve Smale to prove the h-cobordism theorem; from which follows the Poincaré conjecture in dimensions  , and the classification of smooth structures on discs (also in dimensions 5 and up). This provides the foundation for surgery theory, which classifies manifolds in dimension 5 and above.

, and the classification of smooth structures on discs (also in dimensions 5 and up). This provides the foundation for surgery theory, which classifies manifolds in dimension 5 and above.

Given two oriented submanifolds of complementary dimensions in a simply connected manifold of dimension  , one can apply an isotopy to one of the submanifolds so that all the points of intersection have the same sign.

, one can apply an isotopy to one of the submanifolds so that all the points of intersection have the same sign.

History

The occasion of the proof by Hassler Whitney of the embedding theorem for smooth manifolds is said (rather surprisingly) to have been the first complete exposition of the manifold concept precisely because it brought together and unified the differing concepts of manifolds at the time: no longer was there any confusion as to whether abstract manifolds, intrinsically defined via charts, were any more or less general than manifold extrinsically defined as submanifolds of Euclidean space. See also the history of manifolds and varieties for context.

Sharper results

Although every  -manifold embeds in

-manifold embeds in  , one can frequently do better. Let

, one can frequently do better. Let  denote the smallest integer so that all compact connected

denote the smallest integer so that all compact connected  -manifolds embed in

-manifolds embed in  . Whitney's strong embedding theorem states that

. Whitney's strong embedding theorem states that  . For

. For  we have

we have  , as the circle and the Klein bottle show. More generally, for

, as the circle and the Klein bottle show. More generally, for  we have

we have  , as the

, as the  -dimensional real projective space show. Whitney's result can be improved by showing that

-dimensional real projective space show. Whitney's result can be improved by showing that  unless

unless  is a power of 2. This is a result of Haefliger–Hirsch (

is a power of 2. This is a result of Haefliger–Hirsch ( ) and C.T.C. Wall (

) and C.T.C. Wall ( ); these authors used important preliminary results and particular cases proved by M. Hirsch, W. Massey, S. Novikov and V. Rokhlin, see section 2 of this survey. At present the function

); these authors used important preliminary results and particular cases proved by M. Hirsch, W. Massey, S. Novikov and V. Rokhlin, see section 2 of this survey. At present the function  is not known in closed-form for all integers (compare to the Whitney immersion theorem, where the analogous number is known).

is not known in closed-form for all integers (compare to the Whitney immersion theorem, where the analogous number is known).

Restrictions on manifolds

One can strengthen the results by putting additional restrictions on the manifold. For example, the n-sphere always embeds in  – which is the best possible (closed n-manifolds cannot embed in

– which is the best possible (closed n-manifolds cannot embed in  ). Any compact orientable surface and any compact surface with non-empty boundary embeds in

). Any compact orientable surface and any compact surface with non-empty boundary embeds in  though any closed non-orientable surface needs

though any closed non-orientable surface needs  .

.

If  is a compact orientable

is a compact orientable  -dimensional manifold, then

-dimensional manifold, then  embeds in

embeds in  (for

(for  not a power of 2 the orientability condition is superfluous). For

not a power of 2 the orientability condition is superfluous). For  a power of 2 this is a result of A. Haefliger-M. Hirsch (

a power of 2 this is a result of A. Haefliger-M. Hirsch ( ) and F. Fang (

) and F. Fang ( ); these authors used important preliminary results proved by J. Bo'echat-A. Haefliger, S. Donaldson, M. Hirsch and W. Massey.[1] Haefliger proved that if

); these authors used important preliminary results proved by J. Bo'echat-A. Haefliger, S. Donaldson, M. Hirsch and W. Massey.[1] Haefliger proved that if  is a compact

is a compact  -dimensional

-dimensional  -connected manifold, then

-connected manifold, then  embeds in

embeds in  provided

provided  .[1]

.[1]

Isotopy versions

A relatively ‘easy’ result is to prove that any two embeddings of a 1-manifold into  are isotopic. This is proved using general position, which also allows to show that any two embeddings of an

are isotopic. This is proved using general position, which also allows to show that any two embeddings of an  -manifold into

-manifold into  are isotopic. This result is an isotopy version of the weak Whitney embedding theorem.

are isotopic. This result is an isotopy version of the weak Whitney embedding theorem.

Wu proved that for  , any two embeddings of an

, any two embeddings of an  -manifold into

-manifold into  are isotopic. This result is an isotopy version of the strong Whitney embedding theorem.

are isotopic. This result is an isotopy version of the strong Whitney embedding theorem.

As an isotopy version of his embedding result, Haefliger proved that if  is a compact

is a compact  -dimensional

-dimensional  -connected manifold, then any two embeddings of

-connected manifold, then any two embeddings of  into

into  are isotopic provided

are isotopic provided  . The dimension restriction

. The dimension restriction  is sharp: Haefliger went on to give examples of non-trivially embedded 3-spheres in

is sharp: Haefliger went on to give examples of non-trivially embedded 3-spheres in  (and, more generally,

(and, more generally,  -spheres in

-spheres in  ). See further generalizations.

). See further generalizations.

References

- Hassler Whitney; collected papers. Hassler Whitney, James Eells, Domingo Toledo. Nelson Thornes, 1992

- Lectures on the h-cobordism theorem. John Milnor. Princeton University Press. 1965

- Embeddings and immersions, by Masahisa Adachi, translated by Kiki Hudson

- Skopenkov, A. (2008), "Embedding and knotting of manifolds in Euclidean spaces", In: Surveys in Contemporary Mathematics, Ed. N. Young and Y. Choi, London Math. Soc. Lect. Notes. 347 (2): 248–342, arXiv:math/0604045